Why Do VCs Make Startups Pay Their Legal Fees?

One of the most annoying surprises many founders encounter during fundraising is when they finally get a term sheet, only to discover a clause buried towards the end specifying that the startup must pay the investor’s legal fees.

WTF…?

This moment of shock happens so often that, every few months, a new thread pops up on social media decrying the widespread practice.

The initial post is inevitably followed by a pile-on of founders and armchair pundits dunking on greedy VCs. Then come the proud interjections of “founder-friendly” investors bragging about how they don’t make founders pay their legal bills (“not like those other guys…”).

What’s the deal here? How common is it for VCs to make founders pay their legal bills? Why is that even a thing (and what should you do about it)?

Why Do VCs Ask Founders to Pay their Legal Fees?

Let’s start off with the basic question of why VCs do this to begin with.

Don’t VCs have a lot of money?

If a VC is putting $5M into my company, why do they need me to pay $25K for their lawyers?

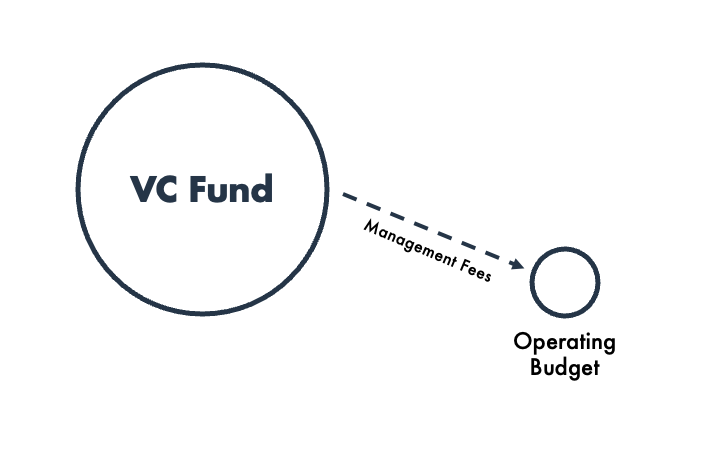

Venture capital firms actually have two distinct budgets:

1. The fund budget (the money a VC invests in companies)

2. The operating budget (the money a VC uses to operate the firm)

Whenever we talk about the size of a VC (e.g. “VC X is a $100M fund” or “VC Y is a billion-dollar firm”), what we’re referring to is the fund budget. Most founders are shocked to discover that the operating budget for a typical venture capital firm is only a tiny fraction of the fund size.

The majority of VC firms have only one source of revenue: management fees (the fees that a VC charges LPs to invest and manage their money). The standard management fee for VCs is 2% per year. Let’s do the math on that:

A VC managing a $100M fund has an annual operating budget of $100M x 2% = $2M / year

A VC managing a $250M fund has an annual operating budget of $250 x 2% = $5M / year

A VC managing a $1B fund has an annual operating budget of $1B x 2% = $20M / year

(For the purposes of this post, I’m not going to worry about billion-dollar funds — since those are pretty healthy budgets) — instead, I’ll focus on the more typical-sized funds that you’ll encounter as a founder.)

If a $100M VC firm did 8 deals each year that incurred $25K in legal fees, they would be paying 8 x $25K = $200K / year in deal-related legal fees. If they paid those fees from their operating budget, it would be about 10% of their annual budget. That’s a lot for any business — especially one that has no ability to increase it’s revenue.

Cry Me a River — Why is This My Problem?

I know, I know. This probably feels like me asking you to play a very teeny, tiny violin for the “poor, starving” VCs. But if you step back for a moment, what we’re really talking about is balancing budgets.

I promise you that VCs don’t like paying legal bills any more than founders do. All of the VCs I know would much rather spend their limited operating budgets on finding and supporting founders than paying lawyers. They also don’t want you to do it.

Seriously.

The last thing any investor wants to do is hand you a bunch of money and have you turn around and spend it all on legal bills. In most situations, that’s not helping anyone win (except maybe the lawyers).

What if I told you that for all the bluster, this isn’t strictly about VCs getting founders to pay their legal fees?

It’s about two things:

Getting the LPs who invest in VCs to pay their legal fees

Getting the prior shareholders who invested in the company to pay their legal fees

How VCs Get LPs to Pay their Legal Fees

I mentioned before that most VCs have limited options when it comes to increasing their revenue. But there are two ways that they can offload these expenses.

The most straight-forward way of doing this is to bill the legal fees back to their LPs as a “fund expense”. In venture capital, fund expenses are the costs of running and managing the fund, which include management fees, administrative costs, legal and accounting fees, and due diligence expenses. In other words, a VC firm can simply pass along the legal fees to the VC fund and get reimbursed. Case closed.

From a founder’s perspective, this is perfect. But it’s not ideal for the VC, for two reasons:

It directly reduces the amount of “investable capital” that the VC has (i.e. the amount of money that a VC has available to invest in startups).

The VC has no control over the scale of those legal expenses.

Many founders presume that if the legal diligence and closing costs get too high, then it must be the fault of the VC. But there are many reasons outside of the VC’s control that can lead to unusually high legal fees, including:

Inexperienced legal representation for the startup

Complex cap table situations that need to be resolved as part of the funding

Amendments to preexisting legal documents that need to be made

Multi-country complexities

IP issues

(One could obviously argue that a VC should know what they’re getting into before legal closing starts, but this isn’t always the case — particularly if a founder left out crucial details or didn’t realize that a particular situation might cause problems during closing.)

Which leads to the second option: offload the legal fees to the company.

How VCs Get their LPs and a Startup’s Shareholders to Pay their Legal Fees

When a VC asks a startup to pay their legal fees, this is what’s actually happening.

A VC can effectively transfer money from their fund budget to their operating budgeting by (1) investing in a startup and then (2) having that startup pay for something on their behalf.

Where do the startup’s other shareholders come in? By virtue of the effective dilution caused by those legal fees being shared across the cap table.

When our hypothetical VC invests $5M in a company and then asks that company to pay $25K in legal fees, the company only ends up with $4.975M. That’s $25K that could otherwise be used to generate a return for shareholders (which includes the incoming VC and all preexisting shareholders — founders, angel investors, other VCs, etc.).

More precisely, the payment of those legal fees results in a loss of value of the startup immediately following the close of the round of $25K (the money paid to the VC’s lawyers from the company’s bank account), which translates into a proportionate loss in the portfolio of each of the startup’s shareholders.

e.g. if our hypothetical startup has a post-financing cap table that is comprised of of 20% New VC, 15% Prior VC, 10% angel investors and 55% founders, then the effective loss of value incurred by each of those groups is:

New VC: -$5,000

Prior VC: -$3,750

Angel Investors -$2,500

Founders: -$13,750

By virtue of this strategy, the VC gains two benefits:

They offload their legal fees to both their LPs and the startup’s other shareholders (without directly reducing their investable capital).

They provide a “soft incentive” to control the overall legal fees (as everyone would now share the pain of out-of-control legal fees).

One More Thing…

There’s one additional (subtle) point to make about this that might not be apparent:

Regardless of how their legal fees get paid, the VC will ultimately end up paying a proportion of the startup’s legal fees (by virtue of the fact that those fees are typically charged after the round closes).

One could argue that the incoming VC will have taken into account the value of the startup post-legal fees when negotiating a valuation, but that’s never actually the case. So if each side ends up with $25K in legal fees — which isn’t unheard of — those fees are proportionately paid by all of the shareholders:

New VC: -$10,000

Prior VC: -$7,500

Angel Investors -$5,00

Founders: -$7,500

(For the VC, this is still very much a win, but it’s not quite the “slam-dunk” that folks who argue about this practice being founder-unfriendly might have you believe.)

What About the VCs Who Don’t Make Startups Pay Legal Fees?

I mentioned at the start of this post that whenever a social media thread on startup legal fees gets going, it inevitably becomes a “me too!” list of VCs bragging about how they don’t do that.

Guess what? A lot of those investors are Pre-Seed VCs. And almost all Pre-Seed VCs invest on SAFEs.

In other words, many of the VCs bragging about how they don’t make founders pay their legal fees generally don’t incur any legal fees when they make new investments.

When I was a partner at Panache Ventures, we did not charge founders legal fees related to our investments. We could do that without reducing our investable capital because almost all of our deals were done on a standard SAFE with a standard, pre-written side letter. Occasionally, we would incur legal fees when some peculiarities arose in the deal or we were following another lead in an equity round, but those were typically a drop the bucket of our operating budget and not worth passing along (to either the startup or our LPs).

To say it differently, a Pre-Seed VC bragging that they don’t charge founders legal fees is like someone puffing their chest after buying you lunch — when all you ordered was a $3 coffee.

“I insist…”

There are absolutely some VCs that don’t ask startups to pay their legal fees, but it’s still relatively rare (and mostly done by established firms with more substantive operating budgets and/or larger funds).

Tips for Founders

Let’s wrap this post up with a few quick tips:

You should expect VCs to ask you to pay legal fees on equity rounds. Generally, this starts at Seed or Series A.

If it’s your first equity round, the costs should be relatively low (as most countries have standardized agreements). Of course, this assumes that you’re coming in with a relatively straight-forward situation.

Most term sheets that ask you to pay legal fees have a cap. That’s good for everyone.

Most reputable legal firms offer fixed pricing for early fundraising rounds.

Make sure your legal team has experience working with startups. Nobody wants you to end up with a giant legal bill because of inexperienced lawyers marking up standardized documents.

If an investor asks you to pay their legal fees on a SAFE round, it may be a red flag. Ask them why they included that clause.

If a Pre-Seed VC wants to do an equity investment instead of a SAFE round, ask if they’re willing to pay the associated legal fees (I personally have no qualms about Pre-Seed equity rounds, but if you’re in a competitive situation where the other offers are all on SAFEs, don’t be afraid to bring this up).

Last but not least, if you’re really annoyed by this, you can always ask the VC to increase the round size to neutralize the effective dilution. Usually, this is a small fraction of the round size — so it might not be the hill to die on if there are other, larger issues to negotiate — but it’s certainly an option.

Bottom line, this practice is neither completely innocuous to founders nor is it a nefarious plot hatched by greedy VCs to take advantage of them.

At the end of the day, the goal on all sides is to get across the finish line and get back to building your business. And everyone wants you to have as much money as possible to do that.