Want People to Say Yes? Listen to Them.

I had been trying for weeks to get an introduction to a well-known founder-turned-angel investor. Finally, I was able to find a friend willing to forward my request for introduction email. A few hours later, a successful introduction landed in my inbox followed quickly by an email response from the angel 🙌.

I opened his email and saw the following:

“Call me. 415-XXX-XXXX”

Caught off-guard by his directness and unsure of what to do, I sent a polite response thanking him for his time and offering to schedule a call.

I never heard from him again.

At the time, I was so used to the choreographed dance of introductions and scheduling that my mind was completely broken by a stranger telling me to just “call him”. That was 15 years ago, long before I understood Silicon Valley’s paradox of time:

In Silicon Valley, most people in places of power, influence and experience genuinely want to help up-and-coming founders, but their work and obligations leave little to no time for them to do so.

The founders who can solve this puzzle unlock an unfair advantage that can change the trajectory of their startup: access to Silicon Valley’s insiders. And the solution isn’t as complex as you might imagine.

You simply have to make it easy for them to say yes.

A corollary of the paradox of time is that people in places of power, influence and experience who genuinely want to help employ aggressive filtering in order to decide who to help.

The double opt-in intro system is an example of one such filter. Another filter — which is shockingly simple yet trips up many people — is the following: when I tell you how to get my help, do you listen?

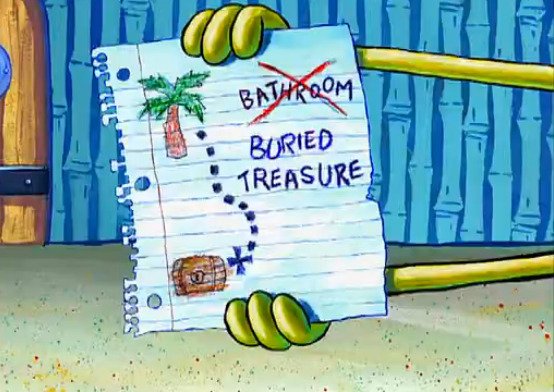

Can you follow the “treasure” map?

In my anecdote above, the investor literally told me to call him. I ignored his instructions and instead did something else (sent him an email to try to schedule a call). While it might seem harsh for him to ghost me after such a simple slight, it makes perfect sense if you look at it through the lens of what he was really saying:

“I’m willing to talk to you but I am unwilling to spend even 5 seconds on scheduling.”

By responding to him with an email, I introduced additional overhead and, thus, failed his filter.

Fifteen years later, I have the privilege of receiving dozens of requests each week for help from founders. But I’m beholden to the paradox of time — as much as I would genuinely like to help each-and-every person who reaches out to me, I simply don’t have enough hours in the day.

So I filter.

And one of those filters is embedded within the responses that I send to the founders I want to help. Responses like:

Asking someone who DM’d me to please send me an email (e.g. “Email me your pitch deck and I’ll take a look.”)

Sending someone a Vimcal link to book a call (e.g. “Click on a slot below to book a call or lmk if none of these work.”)

Pointing them to a blog post I previously wrote that answers their exact question

In each of these cases, I’m trying to minimize the time and effort to get from initial interaction to help. And it’s very much based on how I personally work. For example, my preferred workflow centers around email on my laptop, which is why I redirect as many inbound requests as I can to email.

This is where understanding the dynamics of the relationship is essential to success. If you are the person asking for help, then you should make every effort to fit seamlessly into how the other person works. Jason Lemkin’s advice on asking for in-person meetings is a perfect example of this:

That’s why it’s so essential that you pay attention to the instructions encoded in an offer for help. Especially if it involves changing the communication channel.

If someone responds to your DM asking you to email them, email them.

If someone sends you a Vimcal, Calendly, etc. link to book a call, use that link to book a call.

If someone tells you to just call them, pick up the phone and just call them.

Now that I’m on the other side of the table, I see how frequently people who ask for help ignore (or miss) such instructions. Perhaps it’s because they don’t recognize them for what they are. Perhaps it’s because it’s out of their comfort zone or doesn’t fit the way they prefer to work. Either way, I simply don’t have time to figure it out.

If I ask you to email me something and you instead keep messaging me, I’ll probably stop responding.

If I send you a Vimcal link and you email me back with the time you prefer (instead of clicking the link to just book it), I’ll probably stop responding.

If I send you a link to a blog post that has the exact answer to your question and you instead complain that I’m redirecting you to my blog instead of answering your question, I’ll definitely stop responding.

Not because I’m ornery or don’t want to help you, but because every minute I spend on overhead is one less minute I have to actually help.

That, or I might just be a cranky old man.