Things I Think I Think - Q4 2025

It’s hard to believe how much transpired in the past year. From new administrations to the blistering pace of innovation, 2025 was one for the books.

Now that we’ve made it through our backlogged inboxes, let’s reflect on Q4 and kick off the new year with my latest homage to legendary sports columnist Peter King.

Here are 5 Things I Think I Think - Q4 2025 Edition:

1. The Bifurcation of VC Continues

At this point of the movie, the idea that venture capital has split into two broad categories (multi-billion dollar megafunds and nimble, specialized funds) is no longer up for debate. What’s been fascinating to watch is the behavior of the many funds caught in the middle. These funds are too small to compete on price, too big to embrace the opportunities presented by AI-native companies going after niche markets (read this post on why market matters most to VCs to understand why), and, more often than not, incapable of pivoting to an industry or technological speciality due to the backgrounds of the partners.

Over the past few months, I’ve spoken with multiple institutional LPs who are frustrated at a lack of deployment by some of the VCs they’ve invested in. Unlike the immediate aftermath of the ZIRP crash — when VCs slowing deployment was seen by LPs as a feature, not a bug — the firms caught-in-the-middle have slowed their pace of investment due to an entirely internal reason: they can’t figure out how to adjust their investment thesis to this new reality.

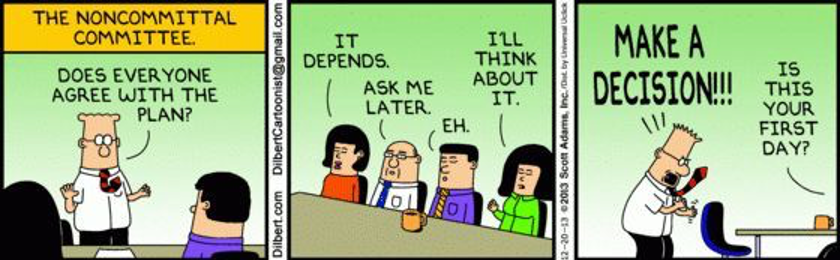

The noncommittal investment committee

The fastest-growing companies are now leap-frogging one or more fundraising rounds (most commonly, the Seed round). That leaves $100M - $250M funds that anchored around Seed — particularly generalist funds — having to reinvent themselves. Do they invest larger amounts of money in fewer companies? Try going downstream to Series A? Or upstream to Pre-Seed?

This dynamic is most noticeable outside of the Bay Area, especially in ecosystems where multistage funds are increasing their presence.

For founders, it’s harder than ever to make sense of local investor behavior. If you plan to fundraise outside of the Bay Area, I recommend adding the following question to every initial investor meeting:

“How many investments did you make last quarter?”

(With followup questions, “what stage were the investments?”, “how much did your firm invest in those companies?” and “were you the lead investor?”)

Don’t be surprised if the answers don’t match what the VC has on their website.

2. SF is Over

It seems like only yesterday that I was trumpeting the return of San Francisco:

Q3 2024: “SF’s slow recovery is accelerating”

Q4 2024: “…we’ve moved from the “innovators” phase of this edition of the San Francisco technology lifecycle to the “early adopters” phase. And that’s a good thing.”

Q1 2025: “San Francisco is still the place to be”

Q2 2025: (I was really excited by Toronto Tech Week and forgot to fanboy San Francisco)

Q3 2025: “…the difference between what’s happening in Silicon Valley right now and what we’re seeing in the rest of the world couldn’t be more stark.”

But I guess it’s all over now…

So what’s happening?

A year ago, I noted that the “maker faire” phase of San Francisco’s AI cycle was over,

“…we’ve moved from the “innovators” phase of this edition of the San Francisco technology lifecycle to the “early adopters” phase. And that’s a good thing.

This isn’t to say that you shouldn’t go to San Francisco in 2025 if you’re a builder — you absolutely should — just don’t expect it to have the same level of serendipity as last year. On the other hand, if you’re a founder a bit further along on your journey who’s looking to meet other high-quality founders focused on building their companies, there’s no better time to come. Just know that you need to be more intentional about your visit and manufacture the outcomes you want.”

What you’re seeing now is the natural result of that shift. The folks who thrived during the meetup and party-heavy experimentation phase of AI’s emergence are finding that, “…there’s nothing too interesting to discuss at a party anymore.”

But it’s not because interesting work isn’t being done. It’s because the people doing interesting work no longer have time to go to parties.

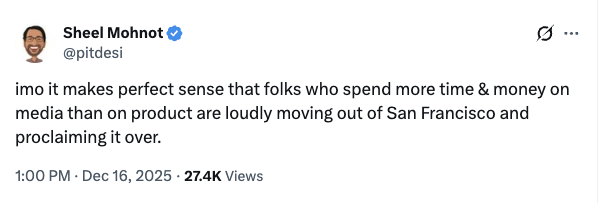

(Side note: a few weeks ago, I wrote about the fact that the tide is starting to turn against rage bait as a strategy for product development and marketing. I suspect that there is a significant overlap in the venn diagram of “Founders who are leaving loudly SF in 2026” and “Founders who rely heavily on rage bait as a strategy”.)

3. The AI Backlash is Here

For a few weeks now, there’s been an increasing amount of coverage about an impending “AI backlash”. Traditional media, social media and countless “2026 predictions” have referenced the turn in public sentiment against AI.

Rather than focus on public sentiment, I thought I’d share some observations on how investors are behaving.

On the one hand, legitimate AI startups are as hot as ever. We’re seeing a degree of preemption and FOMO for hypergrowth AI startups that’s on par (if not greater) than what happened during ZIRP.

On the other hand, I’m seeing an increasing number of investors respond to credible “good-but-not-great” AI startup pitches with a resounding, “meh.”

Overall, it’s clear that the AI honeymoon is over. What’s intriguing to me is that I’m seeing more VC interest in AI startups that are targeting specific niches based on subject-matter expertise (and have real traction points) than in broad, big picture startups.

It’s almost as if vertical SaaS might not actually be dead…

4. The Impact of AI on Junior Roles

Speaking of AI, one of the pervasive narratives in the back half of 2025 was that it was going to kill all of the “junior roles.”

I can’t tell you how many founders I spoke to last year who excitedly proclaimed that they were cutting their staff, getting rid of all of their junior employees and that “AI was the future.” Why hire junior employees when you can just have experienced, senior hires managing teams of agents?

With economists and politicians alike warning of increasing youth unemployment, this trend seemed like a near-inevitability.

Aside from the fact that this didn’t make sense to me as a long-term strategy (if you don’t ever hire junior people, how will you end up with experienced employees when those senior staff members move on?), I couldn’t help but observe a sharp contrast between different companies that I was connected to. At the same time that many CEOs were culling their junior ranks, others were on a hiring binge. I felt a distinct sense of deja vu…

And then it dawned on me: the founders who were proclaiming that AI was end of junior hiring were the same ones who, five years prior, predicted that work-from-home was the future. And you know what they have in common?

They all sucked at managing people.

I’m not suggesting that the job market for new graduates is rosy by any means. But my personal observation is that ambitious, highly-motivated young people with technical skills are in extremely high demand. Especially in companies where there’s a willingness to focus on nurturing, growing and developing talent.

But here’s the zinger: in many cases, Gen Z employees are often more productive than their more experienced colleagues, specifically because they are the first ever AI-native generation. While they may lack experience, their willingness to embrace and utilize AI far outpaces what many of their older colleagues are willing (or able) to do.

Which leads me to two, admittedly knee-jerk, conclusions:

CEOs arbitrarily reducing their junior ranks and/or completely pausing junior hiring is, broadly speaking, a negative signal

CEOs prioritizing the hiring and development of AI-native / Gen Z employees (and, even better, intentionally pairing them with more experienced colleagues) is a positive signal

5. Accelerators are Hot Again

Many of you know that my first stop as an investor was at 500 Startups. Ten years ago, there was genuine competition in the accelerator game. In those days, YC was focused mostly on California, TechStars was championing the “rise of the rest” while 500 was staking its claim to the rest of the world.

But 500 Startups and TechStars both lost the plot, leaving YC to assert its dominance. With YC’s move to four batches a year ago, there’s been little room for competitors to wiggle in. But the tides are turning. Over the past two years, a number of challengers — both new and old — have started to gain momentum.

At one end of the spectrum are the megafunds. Almost all of them now offer some form of accelerator or incubator — either as standalone entities or as platform offerings for their portfolio companies (Canadian investor David Crow wrote a great piece last year about how larger funds are trying to manufacture funnels with this approach).

Most notable amongst the megafunds is a16z, which originally launched its Speedrun accelerator in 2023 as a gaming-focused offering. The firm has since pivoted Speedrun into a generalist accelerator and poured considerable resources into the program (it’s deployed more than $180M to-date and is currently in the process of significantly scaling up its team).

At the other end of the spectrum, we’re seeing a resurgence of both small, dedicated accelerators and offerings from Seed-specialist VCs. There’s Mint from BTV, Pear X from Pear Ventures, and recent entrants like Neo and HF0. Add to that the fact that several international accelerators — most notably, London-based Entrepreneur First — are refocusing their efforts on the Bay Area and it makes for an increasingly crowded field.

With both founders and investors alike looking for an edge, it feels like the pendulum is swinging solidly back from the “hands-off” investing style of the ZIRP era to the more “hands-on” style of years past. At a time when AI is making it cheaper than ever to get a company off the ground, I think we’re going to quickly see a new level of competition amongst credible accelerators (and between accelerators and pre-seed VCs).

And that’s great for founders.