Much Ado About Nothing, H-1B Edition

Let’s jump right in with the biggest news in Startupland™ this week: the announcement that the U.S. is increasing the fee to apply for an H-1B visa to $100,000.

What does this announcement mean for startups in the U.S. and tech ecosystems around the world?

Absolutely. Nothing.

Before you interrupt me to explain how wrong I am, why this changes everything for America, or why your favorite non-U.S. city/state/country stands to benefit, hear me out.

Since President Trump’s announcement last Friday, the internet has been awash with hot takes. Why is Chris Neumann’s any better? For starters, I’ve actually been on an H-1B visa. Moreover, I’ve also hired people on H-1B visas. I’ve worked at big U.S. tech companies and small ones. I’ve been a founder and a VC. None of these facts make me an immigration lawyer by any stretch of the imagination, but they make my understanding of what these visas are, how they’re used by tech companies, and the potential impact of this announcement better than 99% of what you’ve read so far.

So let’s dive right in, starting with a quick primer…

What is an H-1B visa?

Established under the Immigration Act of 1990, the H-1B program enables U.S. employers to temporarily hire highly-skilled foreign professionals in specialized occupations, primarily in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields.

U.S. companies apply for the visa on behalf of prospective employees, who must have at least a bachelor’s degree in their area of specialization. There are three buckets for H-1Bs:

Up to 65,000 petitions each year are granted to general applicants

An additional 20,000 petitions each year are granted specifically to applicants who earned a master’s degree or higher from a U.S. institution

A further category of H-1B petitions, known as cap-exempt petitions, enables universities, government research organizations and certain non-profits to apply for H-1Bs visas outside of the congressionally-mandated annual cap

Note that the H-1B caps described above are for “initial employment” visas (visas granted to people who did not previously have an ongoing right to work in the U.S.) as opposed to extensions/adjustments to existing H-1B visas.

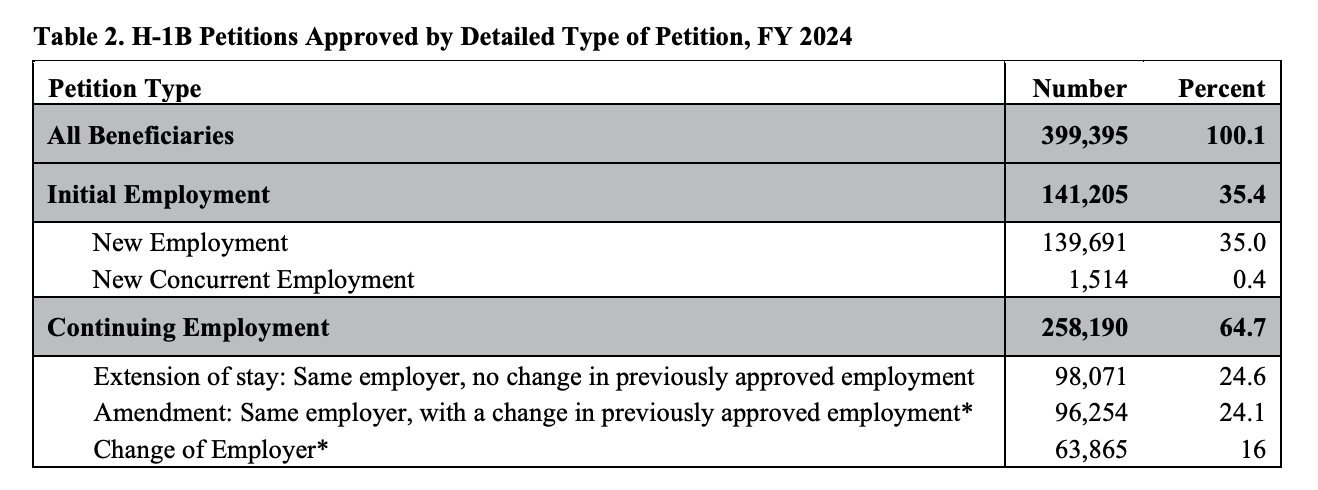

To give a sense of scale, according to the USCIS report to congress on the Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers for FY 2024, 141,205 H-1B petitions were granted for initial employment in FY 2024 (which we can reasonably assume consisted of 65,000 general petitions, 20,000 petitions for individuals with a U.S. master’s degree or higher, and 56,205 cap-exempt petitions), while 258,190 were approved for continuing employment:

Who Gets H-1B Visas?

Contrary to popular belief, H-1B visas are not only used to bring new workers into the U.S. from other countries. In fact, they are mostly used to keep highly-skilled workers in the U.S.

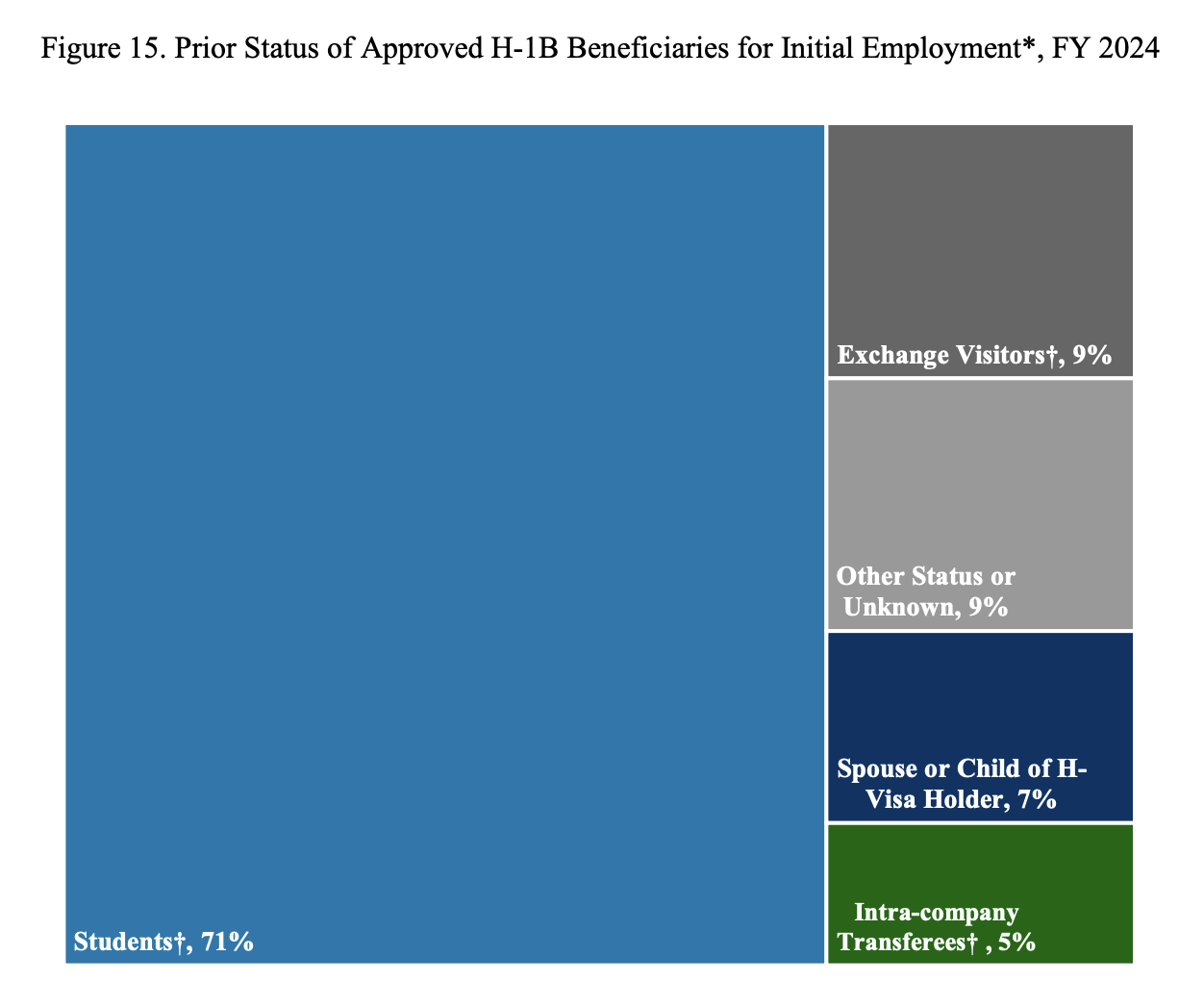

In its report to congress, USCIS noted the following breakdown of the 141,205 H-1B petitions for initial employment that were approved in FY 2024,

“Of the 141,205 petitions approved in FY 2024 for initial employment, almost 46 percent requested consular (or port of entry) notification, and the remaining approximate 54 percent requested a change to H-1B nonimmigrant status for a beneficiary already in the United States.”

In other words, 54% of the approved petitions for “initial employment” H-1Bs went to people who were already in the U.S. on other, non-employment visas. The vast majority of those (more than 71%) were transitioning to H-1Bs from student visas. This is the path that I personally took after graduating from Stanford with my master’s degree (we’ll get back to this point later).

Who Sponsors H-1B Visas?

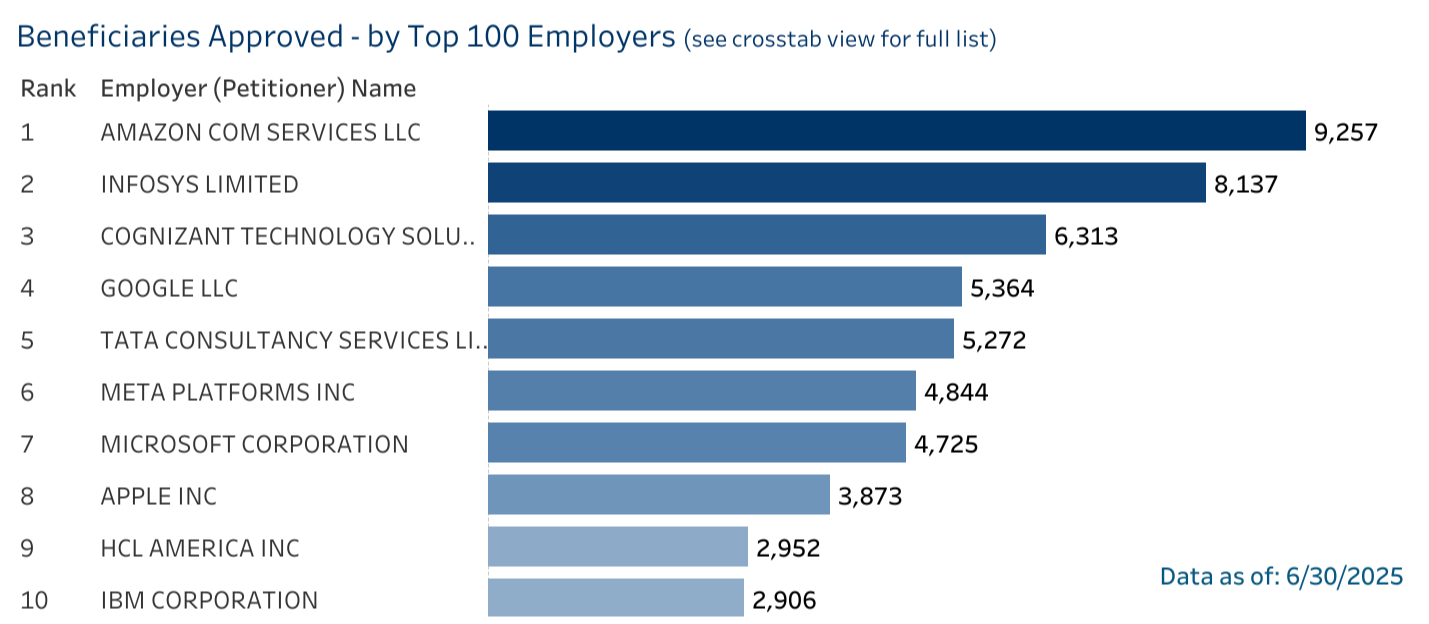

All H-1B visa petitions must be submitted / sponsored by a U.S. company. The significant majority are sponsored by tech companies (which should come as no surprise to most readers). What might be surprising is the types of tech companies that sponsor H-1B petitions. According to the USCIS Data Hub, the top 10 petitioners for FY 2024 included 6 of the largest tech companies in the U.S. (Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, Apple and IBM). The other 4? U.S. subsidiaries of India’s largest consulting companies (Infosys, Cognizant, Tata and HCL).

If you’re wondering why the the topic of H-1B visas is so contentious in the U.S. right now, here it is in one chart:

Despite all of the political rhetoric, the biggest critique of H-1Bs has never really been that U.S. companies use them to hire the best and brightest from around the world in place of American workers. Rather, it’s the perception that foreign consulting firms have been leveraging the program to bring in foreign workers to service U.S. clients (ostensibly at lower wages). I don’t know the degree to which these criticisms hold true, but it certainly doesn’t look good.

Y Combinator CEO Garry Tan has some thoughts on the matter

In fact, if you go through the top 100 list of H-1B petitioners on the USCIS website, alongside a “who’s who” of American tech giants you’ll find a surprising number of U.S. subsidiaries of foreign-owned consulting companies. You know what you won’t find? Actual startups.

Do Startups Hire H-1B Employees?

The short answer is “sometimes”. And that “sometimes” comes with a lot of caveats.

The first thing to note about H-1B visa applications is that “initial employment” petitions take a long time to approve. The approval process (known as the H-1B lottery) only takes place once per year. So depending on when an application gets filed, it could easily take a year or more for an H-1B petition to be approved — if it’s approved at all.

That’s way too long for most startups to wait. Especially when there are other options.

Here’s the reality: the vast majority of U.S. startups don’t hire any foreign workers using initial employment visas. At least, not in their early days.

Why not? Because hiring employees on initial employment visas takes time, costs money and is generally a pain-in-the-ass. It’s far more efficient and effective for startups to hire Americans. No immigration. No complications.

When they do hire nonimmigrant workers, early-stage startups prefer to hire people who already have a visa.

Transferring Sponsorship of H-1B Visas

In FY 2024, 16% of H-1B actions (covering nearly nearly 64,000 individual workers) were transfers of H-1Bs from one employer to another. That’s how a lot of startups hire foreign-born workers. In fact, that’s what happened to me. My initial H-1B petition (approved under the category for individuals with U.S. master’s degrees) was filed by a big U.S. tech company known as Motorola (remember them?). When I joined my former classmates from Stanford a few years later as Aster Data’s first employee, they simply filed the paperwork to transfer sponsorship of my visa over. There was no uncertainty. No long wait. Just some simple paperwork and a (relatively small) transfer fee.

Guess what startups often get when they hire an ambitious young (foreign-born) engineer with a couple of years of experience at Google/Meta/Apple/etc.? A freshly-approved H-1B.

According to USCIS, the fee change announced last week will have no impact on this path:

“This Proclamation does not:

- Apply to any previously issued H-1B visas, or any petitions submitted prior to 12:01 a.m. eastern daylight time on September 21, 2025.

- Does not change any payments or fees required to be submitted in connection with any H-1B renewals. The fee is a one-time fee on submission of a new H-1B petition.

- Does not prevent any holder of a current H-1B visa from traveling in and out of the United States.”

Transferring from Other Visas to H-1B Visas

Another common approach that startups use to hire foreign-born workers is to hire individuals who are already in the U.S. on another visa.

Earlier, I noted that 71% of the H-1B visas granted in FY 2024 to holders of other visas went to individuals who were already in the U.S. on student visas. (That’s 52,385 visas for those keeping track.) How does this work if it can take a year or more to complete an H-1B petition?

It works because F-1 visas come with up to 36 months of post-graduation work authorization.

When it comes to taking advantage of the economic benefits of foreign-born students educated in the U.S., America isn’t dumb. New graduates with designated STEM degrees can legally work in the U.S. for up to 3 years after graduation while their employers petition for an H-1B or other long-term visa on their behalf.

And guess who early-stage startups tend to hire? New graduates.

The change announced last week will have minimal impact on the very healthy pipeline of foreign-born students → U.S. universities → U.S. startups.

(I won’t say zero, as there are likely some individuals who might choose to go to a “big tech” company before joining a startup to increase the likelihood of getting a long-term work visa. But as I described above, that isn’t a new phenomenon.)

It is worth nothing that the change to H-1B petition fees does impact the transition of individuals who begin working at startups on F-1 work authorizations to H-1Bs. But as we’ll see below, there are other potential paths for such individuals. (It’s also worth noting that as of the publishing of this post, there are already discussions underway about potential exemptions to the fee for smaller companies.)

What About Startup Founders? Won’t They Leave?

Probably not.

One important thing to understand is that the H-1B visa isn’t the only employment visa available for tech workers in the U.S. And when it comes to startups, it isn’t necessarily even the best one.

The H-1B wasn’t the only tech-friendly visa established under the Immigration Act of 1990. The Act also established the O-1 nonimmigrant visa, for “the individual who possesses extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics.” In recent years, it has become the preferred option for startup founders and many early employees of startups for three big reasons:

No Annual Cap: Unlike the H-1B, there is no annual cap on O-1 visas.

Shorter Processing Time: Whereas H-1B applications are only processed once per year, O-1 petitions can be processed within weeks of the application being filed, regardless of when the petition is filed.

Certainty: Whereas H-1B recipients are chosen randomly from a pool of qualified applicants as part of a lottery, O-1 visas are granted entirely on the merit of the petition.

It’s only in recent years that O-1s became more common among startups and for a simple reason: they’re harder to qualify for.

To qualify for an H-1B, an individual needs little more than an offer letter and a degree from a qualifying institution. An O-1 is much more involved than that. To qualify for an O-1, the petitioner must provide evidence that the individual is of “extraordinary ability” within their industry:

“The petitioner must provide evidence demonstrating your extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, business, education, or athletics, or extraordinary achievement in the motion picture industry. The record must include at least three different types of documentation corresponding to those listed in the regulations, or comparable evidence in certain circumstances, and the evidence must, as a whole, demonstrate that you meet the relevant standards for classification.“

Guess what? Many startup founders and early employees fall into that category.

So What Does This Change Actually Mean?

At the start of this post, I posed the question, “what does this announcement mean for startups and tech ecosystems around the world?”

If we ignore the politics around this change and focus only on (1) what has been officially announced by the administration (including the most recent clarifications) and (2) how H-1B visas actually work and are used in practice, here is my personal opinion:

1. What Will Be the Impact on Startups?

Despite all of the rhetoric, increasing the application fee for new H-1B petitions will have little-to-no impact on startups in the U.S.

At the early stages, relatively few startups submit initial employment H-1Bs. Those that do can potentially take advantage of other visa programs and/or are likely to have raised enough funding to be able to absorb the cost (considering that many VC-backed startups in the U.S. spend more than $100K on recruiters or legal fees).

Don’t believe me? The best example the Wall Street Journal could find of a startup founder claiming that he would stop using H-1Bs as a result of this change raised $6M in VC funding, employs 11 people — 5 of whom are remote contractors in South Africa and Portugal — and has hired *checks notes* one H-1B worker 🤦♂️.

Still don’t believe me? Here’s what Democratic megadonor Reed Hastings had to say:

Granted, Reed’s take was certainly against the flow when it came to Silicon Valley reactions, but I think it’s the correct one if you reframe the categorization of visas as follows:

H-1Bs will be used for very high value jobs

O-1s will be used for very high value people

2. What will be the Impact on Ecosystems Outside of the U.S.?

As much as politicians and ecosystem advocates around the world rushed to proclaim that this was a massive own-goal on the part of the U.S., I doubt that we’re going to see much (if any) impact in other countries.

Big tech companies in the U.S. won’t blink an eye when it comes to paying this fee. Neither will startups if the jobs are very high value (they will also continue to happily hire workers who spent a few years at a big company in order to get a visa).

We may see a reduction in the number of H-1B applications from consulting companies — who are often driven far more by per-employee margins than other organizations — but that won’t necessarily translate into increases in immigration elsewhere (unless those consulting companies suddenly increase their non-U.S. hiring).

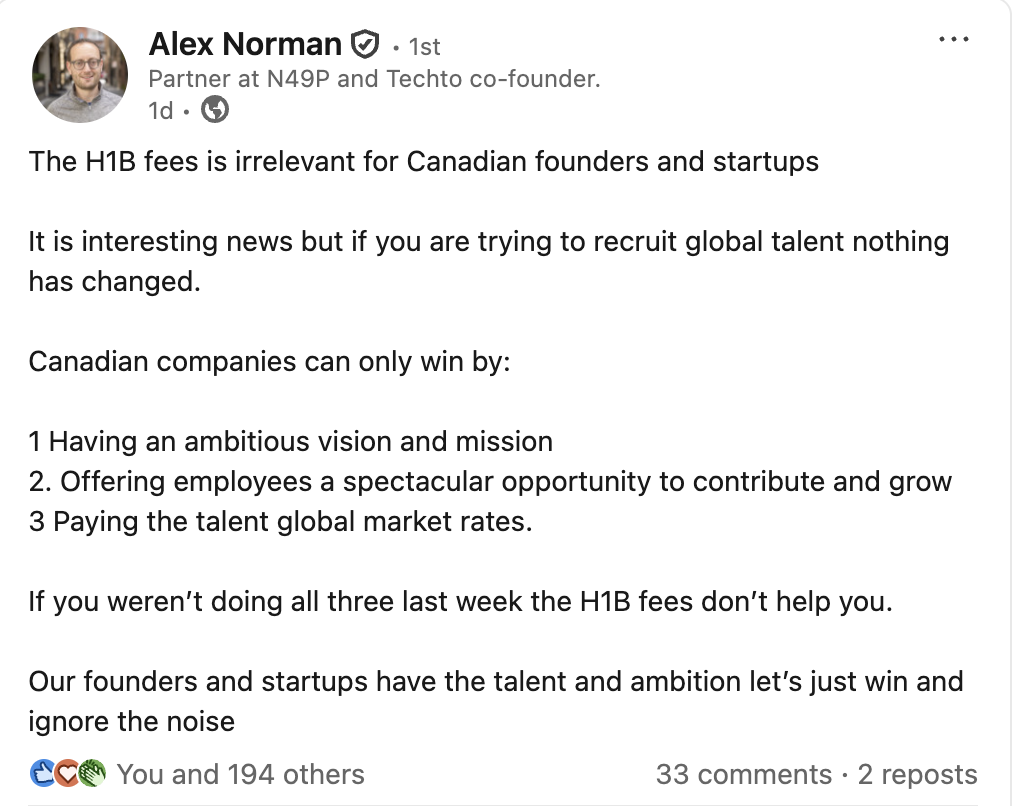

My good friend Alex Norman, Founding Partner of Canadian Pre-Seed firm N49P (who incidentally also previously worked in the U.S. on an H-1B visa) had perhaps the best take on this:

Or as Jack Dorsey once said, “You can worry about the competition…or you can focus on what’s ahead of you and drive fast.”