There is No Such Thing as Pre-Seed Valuation Data

One of the most opaque areas of fundraising — particularly for early-stage companies — is valuation.

Price.

Like most other things, the value of a startup is heavily dependent on the broader market. When you’re buying a house or a concert ticket or a loaf of bread, you typically have access to comparable data. What are other houses in the neighborhood going for? How much are other people paying for Taylor Swift tickets? And so on. So it’s natural to want similar market data when negotiating the sale of a part of your company.

When it comes to evaluating later-stage companies, we generally have access to comprehensive data about the company’s performance as well as established formulas with which to analyze it. Moreover, we have robust data about the overall market, which allows us to make fact-based comparisons (e.g. “what are other companies in industry X with similar metrics and ratios going for?”).

But most pre-seed companies are pre-revenue (and many are pre-traction of any kind), which means we can’t rely on performance data or formulas.

That leaves us with market data. What are other, similar pre-revenue startups being valued at?

But the cold hard truth is that there is no such thing as accurate pre-seed valuation data. And every source that claims to provide it is misleading you.

Why is There No Accurate Pre-Seed Valuation Data?

Until a company is publicly traded, it’s valuation is confidential. That means a startup’s valuation will only become known to outsiders in one of two situations:

The company decides to publicly disclose it

Someone with inside knowledge of the company’s valuation leaks it

The vast majority of founders never publicly disclose their valuation (the rare exception being when a company raises at a ridiculously high valuation and discloses it for marketing purposes), meaning almost all publicly available valuation data has been obtained through leaks.

For later stage companies — especially those that have been involved in secondary transactions — the list of insiders is so lengthy that valuations become widely known. But for early-stage startups, only a handful of parties outside of the company’s walls generally know the valuation…

Who’s Leaking the Data?

If valuation data isn’t being shared by the company itself, who is it coming from?

The vast majority of publicly-available valuation data comes from one of two sources:

VCs and other investors

Companies that provide cap table software

Now, before you grab the pitchforks and run after your investors for sharing confidential information, that’s not exactly what’s happening here. Let’s looks at the two main sources of valuation data to understand (a) what’s going on, and (b) why, even though both of these sources in theory provide good data, the resulting datasets are inherently flawed when it comes to Pre-Seed valuations.

Data from VCs and Other Investors

Many VCs share anonymized data on the investments they make with industry associations and market intelligence companies in order to contribute to broader data sets. That’s generally a good thing for the ecosystem.

Moreover, the data that investors share with industry bodies and market intelligence companies is obviously pretty accurate. The problem is that none of the resulting datasets are anywhere close to being complete/comprehensive at Pre-Seed:

Many VCs do not submit any of their investments to these databases

VCs who make submissions often omit some of their more sensitive (or competitive) investments

International VCs do not submit their investments to these databases

Virtually no angel investors or family offices submit their investments to these databases (so Pre-Seed rounds that do not include at least one VC are almost never included in these datasets)

There seem to be a lot of holes in here…

Data from Cap Table Vendors

Valuation data stored by cap table vendors is more granular and accurate than the data submitted by third-parties (after all, their raison d'être is to keep safe the details of each-and-every investment in a company). The weakness from a reporting and analysis standpoint comes from the inherent limitation of these datasets: each vendor only has data for the companies that use their software.

And the vast majority of Pre-Seed startups don’t use any cap table software.

Most Pre-Seed rounds in North America are done using a SAFE, which means that there’s no issuance of equity at the time of funding. That means there’s no need to formally issue shares to investors (for those too young to remember, Carta was once upon a time known as eShares, as its primary offering was electronic share issuance). Absent a need to issue shares or track company ownership for fiduciary activities, the overwhelming majority of Pre-Seed companies simply keep track their cap table in an Excel spreadsheet — something that most startup law firms will do for free.

Barney invested $500K on this SAFE, which had a $6M post-money cap with a 20% discount…

Pre-Seed Datasets Have Holes…So What?

Why does it matter if the valuation datasets obtained from VCs and cap table providers are incomplete?

Let’s reach back into the cobwebs of our memories and recall a bit of statistics…

A representative sample is a sample from a larger group that accurately represents the characteristics of the larger population. The statistics obtained from a representative sample accurately reflect the results you would achieve by interviewing the entire population.

For a dataset of startup valuations to be representative, the set of startups included in the sample must reflect the broader population of startups. That means it can’t have any significant omissions (i.e. groups with shared characteristics that are excluded from the sample).

The problem with Pre-Seed valuation data is that every single dataset excludes significant cohorts of startups and/or has inherent properties that otherwise make the data set not representative. As a result, the two most commonly-published valuation reports are fundamentally flawed when it comes to Pre-Seed companies:

Quarterly “State-of-the-Market” Reports

Quarterly “state of the market” reports are great fodder for the media. Everyone is eager to read what the average valuation for startups was in Q1. But when it comes to Pre-Seed startups, all of these reports draw their conclusions from datasets that are not at all representative of the market.

Historical Valuation Reports

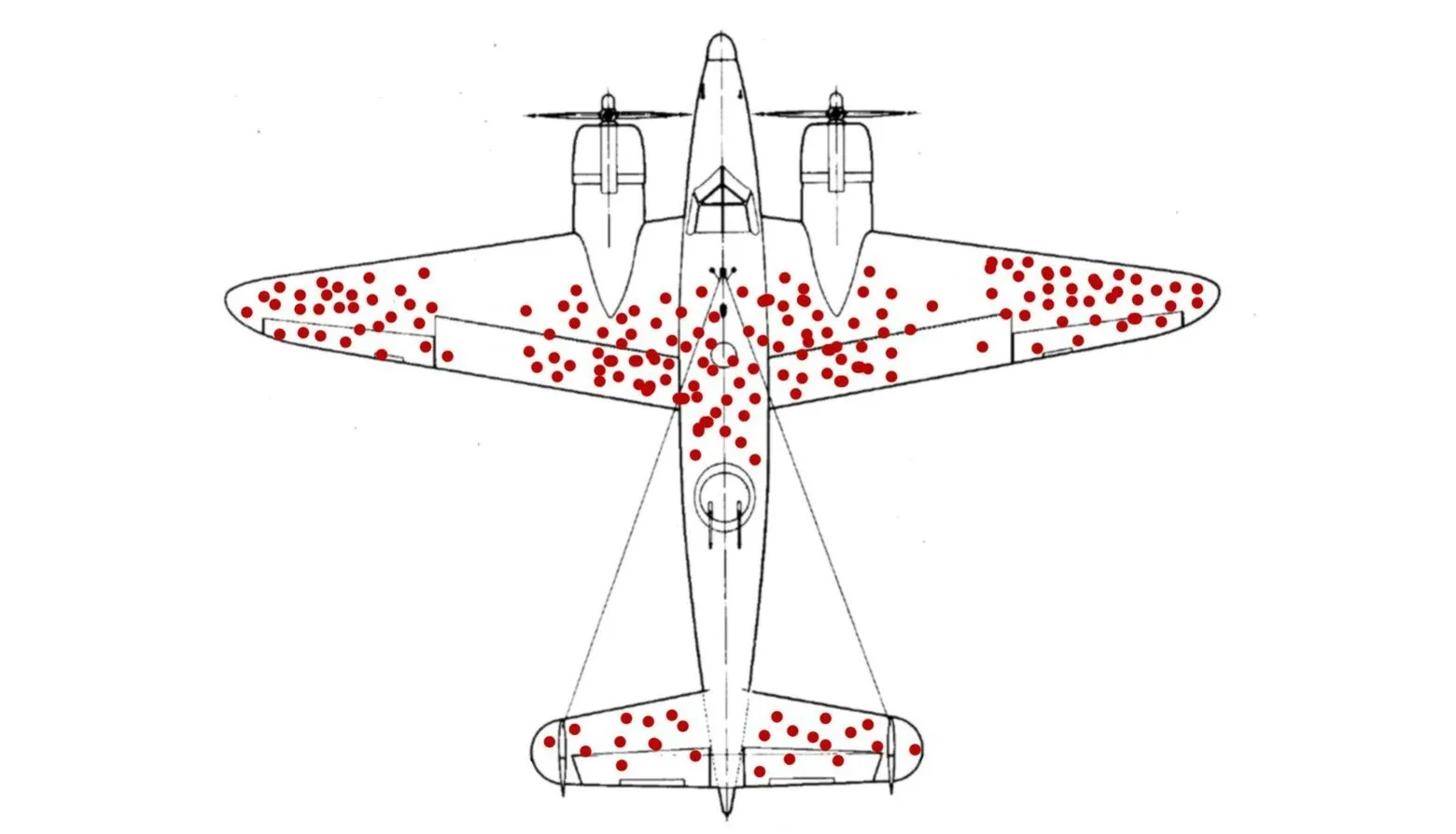

Historical valuation reports show trends over time (“Look! The average valuation of startups in Q1 increased X% year-over-year.”). In theory, these reports are based on comparisons of similar datasets (i.e. each period’s statistics are drawn from datasets with identical weaknesses and limitations). In practice, Pre-Seed datasets become infected a new issue as time goes on: survivorship bias.

Most valuation datasets become more robust over time, as historical data gets submitted to the database. But almost all of the new submissions are triggered by a specific event: a company raising a subsequent round of funding. As time goes on, this skews the valuation data for previous reporting periods in favor of surviving companies and away from those that didn’t last.

What This Looks Like in Practice

Let’s look at some examples of Pre-Seed valuation reports to see what this looks like in practice:

Venture Capital Associations

Venture capital associations, like the National Venture Capital Association of America (NVCA) and the Canadian Venture Capital Association (CVCA) regularly publish reports on startup valuations in their local geographies. The data contained within these reports is sourced exclusively through volunteer submissions from their membership. Here are some recent examples:

In general, these reports are open and transparent about the characteristics of the underlying data. As an example, the latest Canadian Venture Capital Market Overview included the following statement:

“In Q1 2024, Pre-Seed investment activity saw a notable decrease, with only $15M invested across 11 deals.”

While this statement might not seem particularly notable — other than the fact that it seems shockingly low — we’ll see shortly that the simple fact that it includes the number of data points (“…across 11 deals”) sets association reports apart from all other Pre-Seed valuation reports.

Of course, the low number of deals shines a spotlight on the limitation inherent in this type of report: the data comes exclusively from venture capital firms that (a) are members and (b) have volunteered to submit valuation data to the report. As a result, the following categories of Canadian Pre-Seed deals are all likely to be missing from the above report:

Deals by Canadian VCs that are not CVCA members

Deals by Canadian VCs that opted to not submit the details (or failed to submit the details in time)

Deals that did not include any Canadian VCs (increasingly common at Pre-Seed, as more US funds invest early into Canadian startups)

Deals that did not include any VCs (also common at the Pre-Seed stage)

So while the transparency about the size of the underlying dataset is commendable, we have no idea what fraction of the total number of deals done in Canada in Q1 this represents. Thus, we cannot tell if the subsequent analysis is representative of Pre-Seed activity in Canada or not.

(This particular report does not provide any analysis of valuations, but it’s easy to see how the narrow source of data could lead to misleading conclusions — e.g. I’m willing to bet that a dataset of Canadian Pre-Seed deals that excludes those where only US VCs participated is likely to have a lower average valuation than one that includes such deals).

Market Intelligence Companies

The most widely-used valuation reports come from market intelligence companies, like Pitchbook and Crunchbase. The data contained within these reports is primarily sourced from VCs and other investors in startups, though such companies also employ analysts (aka detectives) who try to dig up more details. Here are some recent examples:

Unlike venture capital association reports, market intelligence companies don’t limit themselves by geography or membership. The leading companies try to source data from all over the world.

“$10M-post, you say?”

But if you read through each of the above reports, you’ll quickly notice that none of them are explicit in terms of the number of Pre-Seed deals that underpin their analysis:

PitchBook presents plenty of stats on Pre-Seed deal sizes, without any information whatsoever about how many deals are included in their dataset

Crunchbase and CB Insights both combine angel, Pre-Seed and Seed deals into a single category (and while none of them break out the percentages, Crunchbase at least discloses the aggregate number of such deals)

Crunchbase also deserves credit for being forthright about the fact that there is a delay in regards to their dataset of early-stage funding rounds, with following disclaimer included with their Q1 analysis:

Keep in mind, however, there is typically a pronounced time lag for seed fundings that are added retrospectively to the Crunchbase dataset.

This statement is more than just a tacit acknowledgement that a large portion of their Pre-Seed and Seed data only gets added later. It implies that the impact of the survivorship bias I described earlier is significant when it comes to their early-stage datasets.

Of course, the underlying issue with taking Pre-Seed valuation data from market intelligence companies at face value is that we simply cannot tell whether or not the samples are representative of the Pre-Seed market (and across what dimensions). With venture capital association reports, we know the limitations in the underlying datasets. We have no such transparency when it comes to market intelligence companies. So we can’t even begin to guess at the accuracy of their conclusions.

Cap Table Vendors

Using proprietary data to create content marketing has a long history in the tech world — going back to OKCupid’s epic data blog more than 15 years ago. So it’s no surprise that cap table vendors should look to publish insights about startup valuations.

Angellist and Carta both have a long history of publishing reports on startup valuations. Given the granularity and accuracy of their data, these reports can be incredibly insightful, provided that the reports are based on datasets where the vendor has a significant share of the market. Over the years, Carta has published fantastic insights into later stage rounds. Angellist has similarly shared some of the best data on syndicates and angel-only rounds over the years.

The problem comes when vendors try to publish “authoritative” reports on markets they have relatively little penetration in as a strategy to gain new customers. Case in point: Carta’s recent push into Pre-Seed valuation reporting.

Carta recently published their State of Pre-Seed: Q1 2024 report, which begins with the following statement:

“Since 2020, companies on the Carta cap table platform have signed 101,865 individual SAFEs and convertible notes before raising any priced funding.”

Impressive, right?

The problem is, this big, shiny number says nothing about how many Pre-Seed companies on Carta raised funding in Q1 2024.

The report goes on to provide all sorts of interesting statistics about Pre-Seed deals in Q1 2024, but every single one is presented using aggregates and percentages. There is no indication anywhere in the report about how many data points are included in the underlying dataset. This is in stark contrast to Carta’s State of Private Markets: Q1 2024 report (covering activity starting at the Seed round), which begins with the following statement:

“At current count, companies on Carta closed 1,064 new funding rounds during the first quarter of the year,”

Now, it could very well be that an impressively large number of Pre-Seed startups that raised in Q1 2024 immediately loaded their data into Carta. But I’ve been in the data world for nearly 20 years, and one thing I’ve learned is that if you have an impressive number of data points, you don’t hide it behind an intentionally ambiguous statement.

So, once again, we have statistics being presented as authoritative fact without any ability to determine whether or not the samples are representative of the Pre-Seed market (and across what dimensions).

Why Does it Matter?

Why does any of this matter?

It matters because founders take these reports at face value and incorporate them into their decision process when fundraising.

This particular statistic didn’t match anything I (or any other investor I know) was seeing in the market at the time.

If you’re anchoring your negotiations around statistics from incomplete datasets or datasets that lack context, you’re likely to lose no matter what:

If the reported average is too low, you might be leaving money on the table

If the reported average is too high, you might walk away from a good offer because you think you’re being lowballed

What Can You Do About It?

For starters, anchor your decision process around specific data points instead of the latest click-bait report:

Reach out to founders in your network who recently raised and ask if they’re willing to share their valuation data with you (most are)

Better yet, reach out to founders in your space who’ve recently raised and ask for details on their rounds

At the end of the day, running an effective, efficient high-velocity fundraising process will have far more of an impact on your Pre-Seed valuation than pointing to the latest report. But if you also come armed with specific data points (e.g. “I know that X raised at $7M-post from Y”), your position will be much stronger.

Founders and investors alike would love a comprehensive database of anonymized Pre-Seed valuation data, but I struggle to see how we’re ever going to get one (and, no, blockchain does not “solve this”). So as Mr Miyagi says, “Stay focused.”

(And to all the well-meaning folks publishing Pre-Seed funding reports, please disclose more details on your datasets. It matters. 🙏)